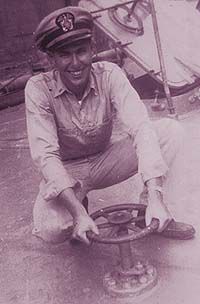

| Robert Neuburg poses for a photo in 1946 when he served on the USS Yucca (Utacarbon) during the Navy vessel’s final incarnation as a ship. |

The Utacarbon, which was launched as part of a war bond drive just after World War I, was a ship that would serve in many incarnations over the years.

The ship’s first 20 years were lived in relative obscurity, but later it would become a part of the largest conflict the world has ever known.

“She was quite a ship,” said Bill Neuburg, who served on Utacarbon in her last days. “She had done a lot of work and hauled a lot of war materials when it ended for her.”

Records about the ship are fairly unclear for the first few years of the vessel’s sailing the seven seas in the 1920s.

The United States Navy ship was eventually sold to the Union Oil Company and records about Utacarbon started to show up in maritime logs.

The ship was used by the company primarily on routes between the continents in the western hemisphere.

In 1941, Utacarbon was requested for use in the Atlantic Ocean to transport fuel to Great Britain, which was losing thousands of tons of shipping to Nazi submarines.

| The USS Yucca docks at Mobile, Ala., just before she was scrapped in 1946. The ship, which had been the Utacarbon until it was transferred to the Russian Navy through the lend-lease program, was later recommissioned as the USS Yucca and used shortly as a tanker hauling aviation gasoline for allied planes being flown home from the Pacific after World War II. The ship eventually was beached and cut up on the Mobile River. |

At the time, the U.S. government decided to let Union Oil keep and operate the ship.

But when the Japanese struck at Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the plans changed. The federal government reversed the decision and told Union Oil to transfer the ship to the Pacific for use by the U.S. Navy.

During the next few months as the ship was readied for use by the U.S. Navy, Hitler’s army attacked the Soviet Union. German troops had driven into the heart of the country and were threatening to crush the Russian military.

Concerned that the Soviets might not be able to hold up their end of the war, the U.S. started sending equipment and supplies to the Soviets, including the Utacarbon. She was rendered into the Russian Navy, and the ship known as the Utacarbon was no more. The vessel was renamed the SS Varlaan Avanson and kept that moniker for nearly three years.

The ship was used to transport aviation fuel from the U.S. to Vladivstock on the Soviet Pacific coast. Interestingly, the vessel was manned by a crew of women that included the captain.

| The last officers of the USS Yucca (Utacarbon) on deck in Alabama. Captain P.L. Carroll stands to the left of the group while Neuburg, a very young cargo officer, stands at the back on the right. |

In March 1945, the Russians returned the vessel to the U.S. and the ship was taken to San Francisco, then onto Stockton, Calif.

The toll on Utacarbon had been heavy. Ice had caused more than $200,000 in damage and the ship was in general bad repair. At this point, the stories about what happened to the ship vary.

One widely circulated account said it would have taken almost a half a million dollars to repair the vessel at a time when the war against Japan was nearly over and that the Navy basically declined to use the ship.

But in recent years, new information has emerged indicating that the Navy actually decided to use the ship in the Pacific war.

The ship had a few repairs, was recommissioned as the USS Yucca IX 214 on July 9, 1945. It was then sent into the Pacific to aide in the upcoming invasion of Japan. But by the time everything was said and done, the ship was too late and the atomic bomb changed the fact that any invasion of the Japanese home islands would ever have to take place.

| The USS Yucca as it sailed toward Mobile, Ala. in the Gulf of Mexico on its last cruise. The flag Neuburg was awarded from the ship is flying above the tanker that was once known as the Utacarbon. |

It was at that point that Neuburg began a journey to not only find the USS Yucca and serve upon her, but ride the ship right to the end of her destiny.

Neuburg, a son of a shipping family from Gloucester, Mass., received his commission on the same day in South Bend, Ind., as the Yucca was recommissioned. He then received orders to serve upon the ship. But it sailed before he could get to California.

To catch up to his assignment, Neuburg boarded a naval transport ship and ended up in the Philippines. He then boarded an attack transport to Youkasuka Naval Base in Tokyo, where the war had recently ended. But when he arrived in Japan the Yucca had departed for Okinawa and he boarded an aircraft carrier that was going to the island to pick up troops that were going back to the U.S.

“I finally caught up with the Yucca at Kadena tanker mooring on Okinawa,” he told the Sun Advocate in a phone interview in October. “I was only 19 and a half years old and I was thrust into being her first lieutenant and the cargo officer as soon as I arrived. Suddenly I was third in command of this 435-foot tanker.”

Shocked by his new found responsibility he was taken back even upon his first inspection of the ship itself. She was basically a rusted hulk that had been abused and misused. And had she had to have gone into combat she would have probably been sunk.

“Little had been done in terms of repairs in California,” he said. “Since it had been designed to carry oil but had carried aviation fuel all those years in transport for the Russians the tanks were very rusted; so much so that I could kick my foot through the sides of them.”

With no cargo of heavy oil or even diesel fuel to coat the tanks from time to time, the shipments of high octane aviation fuel had made the metal of the tanks razor thin.

Other damages and corrosion were apparent all over the vessel, from stem to stern. And since the Russian women crew had been manning it, the ship also had some woman inspired changes as well.

| Robert Neuburg in 2006. |

“All the cabins had been painted in pastel colors and the Navy had done no repainting inside the vessel,” he commented. “So we lived with pale blue, light green an even pink painted quarters for the officers and crew.”

The Navy had however armed the ship with a 3-inch gun, an old World War I 4-inch gun and eight 20 mm anti-aircraft guns. She was still a merchant tanker, but armed.

The captain of the ship at that time was P.L. Carroll and Neuburg said the first trip the ship sailed on was to carry more aviation fuel which they took to Enewetok where they unloaded half the cargo and then they went to Kwajalein, where they unloaded the rest. The fuel was then being used to fuel military planes that were flying back to the United States.

It was then Pearl Harbor bound until about 48 hours before they were to pull into the harbor when the ship ran out of fresh water for the three steam boilers to run on. The crew ended up using salt water to supply the boilers and Neuburg said the engineers had a real mess to clean up inside the boilers after they reached Hawaii.

They left Pearl Harbor and then passed through the Panama Canal on Jan. 6, 1946 on their way to Mobile, Ala. where it was determined she would be beached and then scrapped.

“Her ending was not what one would like to hear,” said Neuburg. “A trip up the Mobile River under steam but assisted by a tugboat. The last orders on the bridge were ‘Hard left rudder-slow speed ahead.’ We then ran her onto a mud bank along with other rusting World War II ships, tied her to a tree, blew off her remaining steam, shut her boilers down for good. We struck her colors, with the commission pennant going to the captain and the last U.S. flag flown above her given to me. The skeleton crew then boarded the tug boat and headed down the river to new naval assignments.”

Neuburg regrets that, in a long engineering career in the U.S. and South America, he somehow lost that flag.

| A Christmas card Neuburg penned from the ship in 1945. Since the U.S. Navy took no official photos of the ship once it was commissioned the USS Yucca, there are no known complete photos of the ship. This drawing shows the entire ship and it’s armament during its last days. |

“She was really a grand old ship and left me with some very lasting memories,” he said. “She served her country well, with a very interesting pre-world war history, as a lend lease vessel to the Russians and lastly as a U.S Navy tanker.”

After being beached on the mud bank near Mobile, the War Shipping Administration that took over the ships after the Navy surrendered them sold the Utacarbon to the Pinto Island Metals Company for scrapping.

The ship was a unique piece of Carbon County history. While Utah and some of its cities have had several ships named after them, Carbon is the only county to have earned that distinction.

And regardless of the name changes at the end of her ocean bound life, the vessel was still the USS Utacarbon, built by hard earned dollars contributed by Carbon County citizens.

Editors note: Today’s article is the last story in a two part series about the Utacarbon.