CELEBRATING 102 YEARS OF GREEK HERITAGE

Residents of Carbon County and people from around Utah celebrated the 102nd anniversary of the dedication of the Greek Orthodox Church in Price with Greek Festival Days July 13-14.

Honored as the 13th Greek church built in the United States and the oldest such house of worship in continuous use west of the Mississippi, the Assumption of the Virgin Mary Greek Orthodox Church is the cultural epicenter for a unique facet of Price history and heritage.

If you had the privilege of growing up in Carbon County, chances are your childhood friends were a melting pot of nationalities. Going to their homes was often akin to traveling to a foreign country. The food, the language, the traces of their homeland was like a warm embrace.

It was an unforgettable experience for people whose families did not share such an eclectic history. A number of prominent Greek Carbon County families eventually blended with Italians, Slovenians and Americans from the area to create a rich, diverse community unique to Utah.

This cohesion and peacefulness witnessed today among people born of these early 20th century migrant families was not always the case.

In 1900, the Utah census claimed one person of Greek birth in the whole state. By 1910, that figure swelled to 4,062, although many Greeks refused to take part in the census and so that number is most likely very low.

Lured to Carbon County with the promise of steady work in the coal mines, many Greeks landed in the county in 1902, at first as strikebreakers during a county-wide coal mine strike.

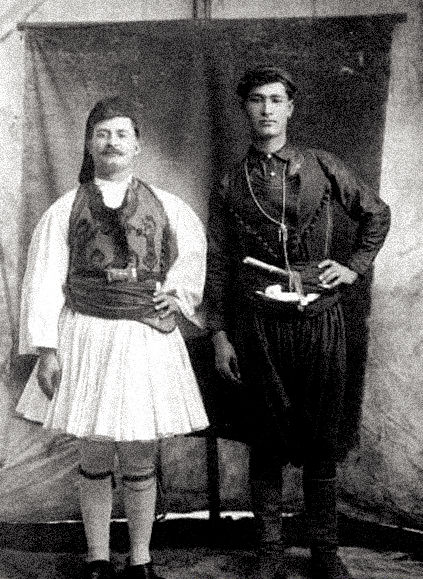

The men came first. Drawn to America by extreme poverty in their native country, these young men were hoping to earn a decent living in the resource-rich lands of America and then return home to Greece.

In many cases, the men ended up staying in America, writing home for wives and children to join them, or in the case of single men, ordering away for “picture brides” from their homeland.

The Greeks became a sought after work force. They were paid below what other miners were making for the same jobs and like other immigrants from distant lands, were segregated into their own “towns” and boarding houses.

Racial rivalries helped to isolate the various groups, too. This segregation was a misguided effort to keep talk of unionization down and keep the individual ethnic groups submissive to the will of the mine companies.

Women were often called into duty to operate Greek boarding houses. These houses provided room and board for up to 10 single men at a time, some of which were likely relatives of the woman’s husband.

Coal mining proved to be hard, dangerous, and back breaking work. While many immigrants stayed with their work in the coal mines, many others sought other ways to make a living. Some became businessmen, opening up stores, bakeries, cafes, grocery stores and Greek coffee houses, while others returned to the life that they knew back home—they returned to raising sheep.

In 1916, the businessmen, the miners and the sheep ranchers got together and pooled their money. They wanted a church, a place to worship and a place to properly bestow the rights of their forefathers upon those who had died on foreign soil.

A site was chosen in Price and construction began. On Aug. 15, 1916 the church was officially dedicated. It was estimated the Greek population of Carbon County was more than 3,000.

In 1922, the Greeks became the target of some truly ugly hatred by the mining companies and the local powers-that-be. In 1902-1903, it was Italians who were seen as inciters of labor unrest.

Ironically, it was the Greeks who came in and bailed out the mining companies. In 1922, the inciters were allegedly the Greeks. A Greek miner named John Tenas was killed by a mine company guard. This event sparked a bloody strike that killed dozens.

Greeks were blackballed or banned from working in any coal mine in the United States. Some were targeted and deported, others were harassed by mining companies, their officials, and their gun-toting henchmen, until they voluntarily left the country.

One Greek miner was driven from the United States simply for professing his attraction to a young, blonde female clerk in the company store. A “hit” was taken out on the man, letters blanketed the country to other mines, and he was forced to flee the country. He barely escaped with his life

At this same time another powerful force reared up in Carbon County—the Ku Klux Klan.

The KKK, whose name, ironically, is derived from the Greek word “kuklos,” or circle, turned their hatred on Greeks, Italians, Slovenians, and Catholics alike.

The KKK burned crosses on a hill near the present day golf course, while the Italian Black Hand organization and the Catholic Knights of Columbus burned circles on an adjacent hillside. That had to look like a unique game of “tic-tac-toe” to bewildered innocents.

After many months of terror, a brave young Greek mother took on the Klan in a Greek neighborhood in Helper. As told by her daughter, the mother took her infant child and her young daughter right into the house where the Klan members were meeting. As it was a closed meeting, the Klansmen were not disguised in their hoods.

The woman marched right up to the front of the room, turned around and pointed at each man seated, saying, “I see you. I know all of you. I and my family will remember every one of you.”

The little girl did as her mother asked, she stood straight and still and with her mother memorized the faces of the men who caused so much hate in their town.

The Klan members sat in stunned silence, so much in shock that the woman and her children were allowed to leave unhindered as they recovered from the surprise.

Klan violence became much more covert after that. The main staging hill for burning crosses was later purchased and became the Slovenian Cemetery.

Besides social unrest, industrial accidents affected migrant coal miners as much as any group.

On March 8, 1924, a devastating explosion occurred at the Castle Gate No. 2 coal mine. Of the 171 men killed that day, 49 of them were Greek.

Many of these miners were laid to rest at a group funeral at the church in Price and buried in the Price City Cemetery, their names jump off their tombstones today like postcards from Price City’s storied past.

Many of the women left behind stayed in Carbon County and made their own living for themselves. These proud women often baked bread or made wine to sell to neighbors.

The history of the Greeks in Carbon County has been fraught with turmoil, with rage and with tragedy, but the beautiful Assumption of the Virgin Mary Greek Orthodox Church, bathed in 102 years of glory, remains a shining example of how faith and heritage can rise above all that.