Heidi’s Promise

M.

It was this lonely letter that might’ve brought a depraved killer to justice from the outset.

But Loretta Jones, a 23-year-old single mother, managed only to scrawl the letters T and O into her own blood as she lay dying on the living room floor of her Price home.

It was July 30, 1970. Loretta Jones had been stabbed 17 times in the back, twice in the chest, and suffered a nasty wound to her throat.

She’d also been raped.

Her 4-year-old daughter was asleep inside their home at 468 E. 4th South when the brutal attack occurred.

Neighbors found her on the front porch the next morning. She told them, “I think my mommy is dead.”

Though a likely suspect was nabbed by police within days of the murder, it took more than four decades before the Loretta Jones case was closed.

It’s an amazing story—a daughter’s unquenchable thirst for justice; the hazy outline of a mother’s guiding spirit; the legwork of a dedicated cop, who closed his first cold case investigation in spectacular fashion and with zero reliance on anything more than old-fashioned sleuthing; and, finally, the confession of a stone cold killer, who having gotten away with murder for 46 years, is today considered a top suspect in a few more.

Pages and pages of ink were dedicated to this story over the years, including in this very newspaper.

On March 18, the near unbelievable circumstances surrounding the Loretta Jones case will be aired before a national audience on cable television.

“On the Case with Paula Zahn,” on Investigation Discovery, Channel 80 for most local cable subscribers, will run an hour-long program on the subject starting at 8 p.m.

The show is likely not the last word in this incredible story.

T is for Tom

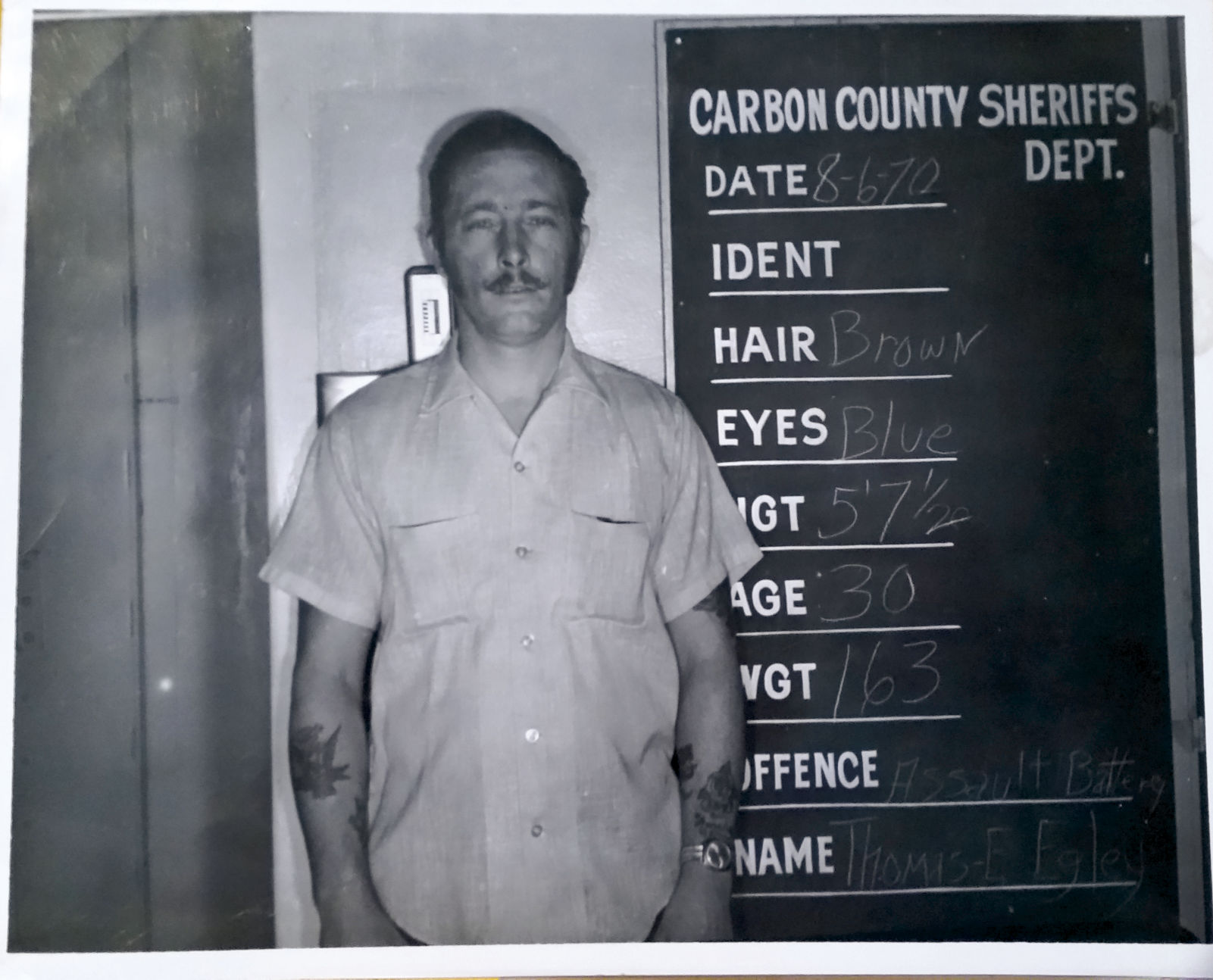

Thomas Edward Egley, offender number 229905, lives confined within the walls of the Utah State Prison’s Oquirrh (pronounced “Oh-kurr”) facility, where the state provides two special dormitories for geriatric prisoners.

At 77, chances are pretty good Egley, previously of Rocky Ford, Colo., will never live free again.

He was sentenced to 10 years to life in Seventh Judicial District Court in November 2016 after pleading guilty to killing Loretta Jones during a court hearing a month prior.

He did not want to cop to sexually assaulting her. Her family accepted dropping the rape charge he faced in order to avoid a painful trial.

Carbon County Sheriff’s Det. Sgt. David Brewer looks forward to the day when he will see Egley again.

He still has some questions for him, little pieces of the puzzle, nagging, personal curiosities about what happened in 1970, how and why.

Brewer doubts he can convince Egley to talk to him again—the detective suspects Egley would clam up thinking he could be prosecuted for something new. After all, in court in 2016 Egley had told Judge George Harmond he was bewildered why anyone in the world cared about what he did 46 years before.

Anything he told Brewer today couldn’t be used against him. At least not in the Loretta Jones case.

Brewer said he will probably give it a shot anyway.

O is for Optimists

Brewer started work on the murder case in 2009, after running into Heidi Jones-Asay at the Helper Arts Festival, a little bit of synchronicity at work. Egley lived in Helper in 1970 and likely disposed of critical evidence in the case there, including burning his bloody clothes in one of the ubiquitous burn barrels used by residents there at the time. He also confessed to tossing the small pocket knife he killed Loretta Jones with into the nearby Price River.

Heidi, or course, was the little girl on the front porch, all grown up.

She had moved from California a few years before, telling friends there she knew who killed her mother and was returning to Utah to solve the case once and for all. Shows like “Unsolved Mysteries” and other cold case dramas intrigued her. So much that she wrote streams of letters to officials near and far looking for help in solving her mom’s case.

Brewer, like most police officers put in that position, was skeptical at first. But he agreed to look into her mother’s case.

Brewer said he began with a handful of newspaper articles and not much else. The case file, for example, had disappeared.

He brought such a fresh perspective to the case, he purposely ignored the fact police arrested a suspect in the case mere days after the murder.

That suspect was Egley, then age 30. And despite Brewer’s reluctance to focus the investigation on him early on, Egley eventually would become the proverbial last man standing.

Police originally brought him in for questioning after the family of a 10-year-old girl reported she’d barely escaped being abducted—a man fitting Egley’s description had attempted to grab the girl while she road her bicycle in the 400 South and 700 East block of Price.

The date was July 30, 1970 and it happened not far from Loretta Jones’ house.

Egley was arrested and spent the next four months in the Carbon County Jail. He was eventually charged with Loretta’s Jones’ murder.

Though the first two letters of his name sat written in blood at the crime scene, none of the investigators or local prosecutors in the case were confident, or perhaps competent, enough to mention it in later court proceedings.

An exasperated local judge eventually let Egley walk. Evidence to make a solid case supposedly just wasn’t there, and, shockingly, none was pursued with any zeal for nearly a half century.

Brewer is no magician, nor is he a psychic. The methods he used to harden the case against Egley in the later stages of his investigation were available in 1970. Example, Egley had a pregnant girlfriend in Helper in 1970 and Brewer eventually tracked her down to Kansas. She shared her recollection of that night of the murder, of Egley coming home late, strangely taking a bath with his clothes on and placing the wet clothes in a bag by the door. He asked if she had any laundry that he could do for her—something he never, ever did. She remembered the details of that night quite clearly, Brewer said.

Brewer heard more stories like these from potential witnesses, including the first Price police officer on the scene that morning Loretta Jones was found.

He told Brewer he recalled the T and the O in the blood. It was the second time someone had told Brewer the story about those two little letters. It was information Heidi wasn’t even aware of until late in the game.

M is for Mislead

Heidi says she always knew it was Egley. And now Brewer was certain of it, too.

But it wasn’t until 2015 that the most critical piece of the puzzle fell into place.

That’s when LuDeen Jones died.

LuDeen was Loretta’s mother, Heidi’s grandmother. She raised Heidi, adopting the little girl in 1973.

Any talk of the tragedy quickly brought LuDeen to tears. Heidi’s family believed Loretta’s murder played an outsized role in the 1974 sudden death of LuDeen’s husband, Parley Jones, a well-liked local contractor.

“You could not talk about it. Everyone in my family believes the stress of my mom’s murder and everything contributed to his heart attack,” Heidi said. “After he passed away we just couldn’t talk about it. All it would do is bring my grandma to tears.”

Inside a corner of LuDeen’s garage sat a few boxes of Loretta’s belongings. Her diaries, which she wrote in every day since she was a young teenager, were there.

Photos the family took of the crime scene once police allowed them back into Loretta’s home filled a family photo album. And it was there. One photograph captures Heidi standing mere feet from where her mother died, blood stains and the police drawn outline of where Loretta’s body lay, are visible in the picture. The T and the O are there, too.

LuDeen kept pages of notes she made shortly after the murder, notes recording the nightmares a young Heidi would recall, or things the little girl would say, such as about hearing those heavy boots stomping through her mother’s living room, or worrying to her grandmother that “Tom was going to get her.”

“Heidi is screaming, crying again. She hears Tom’s boots,’ Heidi recalled one note saying.

Those notes sat in a box in the corner of LuDeen’s garage.

“That garage was kind of off limits. Every chance I got to go snoop, I would,” Heidi said.

Even when Brewer decided he needed to exhume Loretta from her resting place in Elmo, he had to wait for LuDeen.

She was next of kin and she was simply not having it.

When LuDeen died in 2015, it opened the door for that exhumation to take place, because now Heidi was the next of kin and could provide the necessary permission.

Heidi and Brewer knew it was LuDeen, expressing her discontent from beyond this realm, when as Loretta’s remains were lifted from her grave a sudden dusty, hot wind blew through the cemetery, and dark clouds briefly filled the summer sky.

Brewer spent the night in the transport bay at the sheriff’s office with Loretta after she was exhumed.

He hoped the exhumation would uncover usable forensic evidence, or new clues that would strengthen his case.

Heidi wanted that and more. A class ring her mother was buried with now rests on her finger.

Loretta’s remains yielded little new evidence.

But it did one really important thing: it gave Brewer a chance to scare the hell out of Thomas Edward Egley.

A July 10, 2016 headline in the Salt Lake Tribune reads, “Police are closer to cold-case’s closure after trove of new evidence ‘by the truckload’ turns up in 1970 stabbing death of Price woman.”

A Sun Advocate article from July 5, 2016 carries a headline reading “Homicide cold case evidence handed to attorney general.”

Brewer made sure these stories and more got back to Rocky Ford, Colo., where Egley was living and where he’d told Brewer during an earlier face-to-face interview that he had nothing to do with Loretta’s murder.

It wasn’t long before Brewer and Heidi—who started a Facebook page titled “Justice for Loretta Jones”—began hearing from people in Rocky Ford.

One said she feared Egley was suicidal. Another claimed Egley told people he was going to prison.

End game

Brewer let Egley simmer in his own guilt.

When the killer reached a slow boil, the trap was sprung. A key informant, a neighbor of Egley’s, actually encouraged Egley to talk to Brewer again in 2016. The previous meeting between cop and killer occurred six years earlier, when Egley denied killing Loretta Jones.

Brewer along with another detective was in Rocky Ford for a while watching and waiting for the informant to signal that another interview was on. When it went down, it was almost anticlimactic.

Egley said he did it. But it was a long time ago. So what.

The toughest thing Brewer says he ever did was walking out of Egley’s house that day without the killer in handcuffs. Local prosecutors had repeatedly refused to take the case previously. So Brewer sidestepped local officials and took Egley’s confession to the Utah Attorney General’s Office. They grabbed at the chance to prosecute.

U.S. Marshals arrested Egley on Aug. 18, 2016. He was extradited to the Carbon County Jail and by October pleaded guilty.

Loretta Jones’ murder was officially solved.

While her case will likely live on in the annals of cold case successes for a long time, the story isn’t quite over for Egley.

Killers like him don’t usually strike once. Though Brewer admits Loretta Jones was probably his first killing, his heart says there are probably more victims tied to Egley.

In October 2017, it would seem something was afoot in Rocky Ford. Television news cameras had captured Colorado Bureau of Investigation agents combing Egley’s old home for evidence.

Law enforcement sources there told media outlets they were investigating new clues in the 1982 disappearance of two high school girls, Victoria Sanchez and Yvonne Mestas, both only 15 years of age.

They were last seen walking home from Rocky Ford High School on Nov. 1, 1982.

It could fit a pattern Egley started along in 1970. Brewer says he always believed the little girl on the bicycle was Egley’s intended target. Not Loretta Jones.

National cable show to air story of 1970 cold case murder of Price woman

The 1970 booking photo for Thomas Edward Egley.