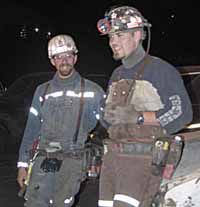

| Underground workers Arlyn Williams and Denny Erickson prepare to go into the Andalex coal mine to start a shift. The coal mining profession frequently experiences growing or shrinking numbers due to slack markets and technology changes. Nationally, the demand for coal miners is presently increasing and, in some places in the United States, the shortage of trained personnel is reaching the critical stage. |

While many people may have written off mining as a vocation of the past, the reality may be that coal production and related industries may become one of the largest growth sectors in the future.

The reasons for forecast are varied and complex, but two factors are weighing heavily in the balance for coal mining jobs to return to the past glory.

One is the fact that today’s coal miners are getting older, with a large group of them more than 50 yearsof age, and younger replacements seem to be few and far between.

Second and more important, the United States is facing an energy crunch in the next few years that will bring coal back into the limelight for power generation and, possibly, even large scale gasification at some point.

While some people may think that exports are the biggest piece of the action in the coal industry, that is not necessarily true.

So far this year the United States exported (through the end of the second quarter) 24,943,405 tons of coal to other places in the world, while last year during the same period of time the total was 19,967,576. That is a 24.9 percent increase.

The most coal is exported to Canada, with Europe fairly close behind and Asia about a million tons behind Europe. The figures may seem like big amounts to a layman that views the industry, but they are nothing compared with the past.

“The problem with the present numbers is that the United States used to export 100,000 million tons of coal per year,” said Sam Quigley, vice president of operations for Andalex Mining. “Utah is now exporting very little coal outside the country. The world price became so depressed that it basically forced Utah out of the export business.”

The United States is currently importing coal for domestic needs in some places, pointed out Quigley The shortage of mined coal is showing up not only in the west and in the nation, but in countries across the world.

Nationwide , there appears to be a coal boom going on, particularly in the hiring segment.

In some eastern locales, companies are advertising in every way possible to attract workers to mines.

The advertising methods include using billboards and even going to such lengths as towing banners behind planes in vacation spots southcentral state coal workers frequent. As the present miners get older and retire, this trend could intensify even more.

Some say Carbon County, in particular, could benefit from this potential boom in coal demand, not only from the royalties and mineral lease monies, but from the good jobs it could provide. In the past few months the Sun Advocate has been filled with classified ads of companies looking for miners, particularly those with experience. But with so many mines closing or being idle in the last few years, many of those that manned those mines have moved away, leaving the real estate market in the area more depressed than almost any other market in Utah. In fact so many have moved away and found other employment, that the coming market could favor a whole new generation of coal mine workers.

“There is a serious shortage of labor for mine positions right now,” Quigley explains. “But it’s not due to more production or the higher prices for coal. It’s due to the fact that the mining conditions are getting more difficult and we need more labor to produce the coal.”

Quigley said the coal industry has taken such a beating from low prices in the past 30 years that the industry in the short term may not be able to add up the numbers to supply the coal that will be needed. Much of the coal that is produced in Utah is used within the state, particularly for power generation.

Coal mining today is a far cry from the past. The number of coal miners in the United States in the first half of the 20th century was between 500,000 and one million and possibly even more at some points. The work was hard, and largely human labor driven. As mining machines were developed those numbers started to drop because mechanization replaced them. By the 1960s continuous mining equipment was in general use and when long wall mining appeared the numbers of miners dropped even further. By 1990 the numbers were in the 160,000 range, but that was not the end of the decline. Mixed with the mechanization came low prices due to lower demand and consequently more mine closings due to the depressed profits. According to the federal Mine Safety and Health Administration, there were only about 100,000 coal miners left in the United States at the end of 2003.

But the national energy crunch could change that as coal becomes more in demand. However, that same energy crunch and higher prices it has caused have already had an undesirable effect on the coal industry as well as everyone else.

“The energy crunch has hurt us cost wise,” said Quigley. “Our steel costs are up 106 percent over what they were and in a mine you use steel for everything from bolting systems to equipment parts. And the direct fuel costs to run equipment has hurt us as well.”

He pointed out a number of instances where equipment costs are growing by leaps and bounds. Recently his company checked on buying a new roof bolter machine and the price was $320,000. They decided to put it off for awhile and when they rechecked the price the same machine had gone up to $500.000.

While the picture for increased production in Utah may come from new or idled mines opening, such as Skyline, the Emery Mine and the Lila Canyon Mine, which all will require miners to work at them, another problem has arisen nationally concerning new miners. That problem has to do with training and training systems.

Over the past few years most colleges that have offered mining classes and instruction for supervisors, engineers and inspection personnel have either cut out their programs or cut them way back. The College of Eastern Utah has been phasing out its mining department, but the training has been taken over by UCAT (Utah College of Applied Technology) and is actually being done in the same classrooms it was before on the CEU campus.

Quigley said what has been happening nationally in terms of experienced miners is true here, too. There is a lack of expertise in the work force looking to be hired in all phases of coal mining locally. That makes the training programs all important.

Obviously the price of coal will determine what will happen nationally for coal miners. A year ago coal was going for $17 a ton, now it is $35.

“I have heard that in some places in the east the spot price is $60 per ton,” said Quigley. “But that is really a function of the fact that suppliers can’t provide it.”

Around 30 years ago there were nearly 30 companies operating mines in the local area. Now there are only five in the county.

But regardless of whether more mines open or not, or whether other companies move in to take the hard black energy out of the ground, the hiring situation looks good for those who want to go to work in mines, and bleak for those that need them.