A first-person travelogue

We left Price in the early afternoon, stopping at J.B.’s for lunch before the trip to Buckhorn Wash and beyond.

Dr. Steve Lacy and Terry Carter, a self-styled treasure hunter, had traveled that morning from up north and had already visited a few historical sites around town before picking me up at the Sun Advocate.

I had my backpack, with tent, sleeping bag and pillow, and frankly was most anxious to see the night sky.

On the agenda was two days of historical sight-seeing, retracing the steps of outlaws Butch Cassidy and Matt Warner as well as a few bit players in Southeast Utah’s own Old West saga.

Lacy, as readers of this newspaper know, is a historian with deep ties to Carbon, Emery and San Juan counties. His works include “Last of the Bandit Riders…Revisited…Again” and “Posey: The Last Indian War,” as well as other books and stories of historical note.

Carter filmed Lacy during the entire trip, capturing stories and video for his YouTube channel, which features a number of videos on the Old West as well as more colorful subjects, such as Bigfoot, the Nephilim giants, and Egyptian symbols found scattered throughout the Southwest.

Traveling along Utah’s SR-10 south into Emery County, our first stop was inside the popular Buckhorn Wash area inside the Swell.

TIME TO KILL

Nary a cloud was in the bright blue sky, when we pulled up alongside a grove of cottonwood trees.

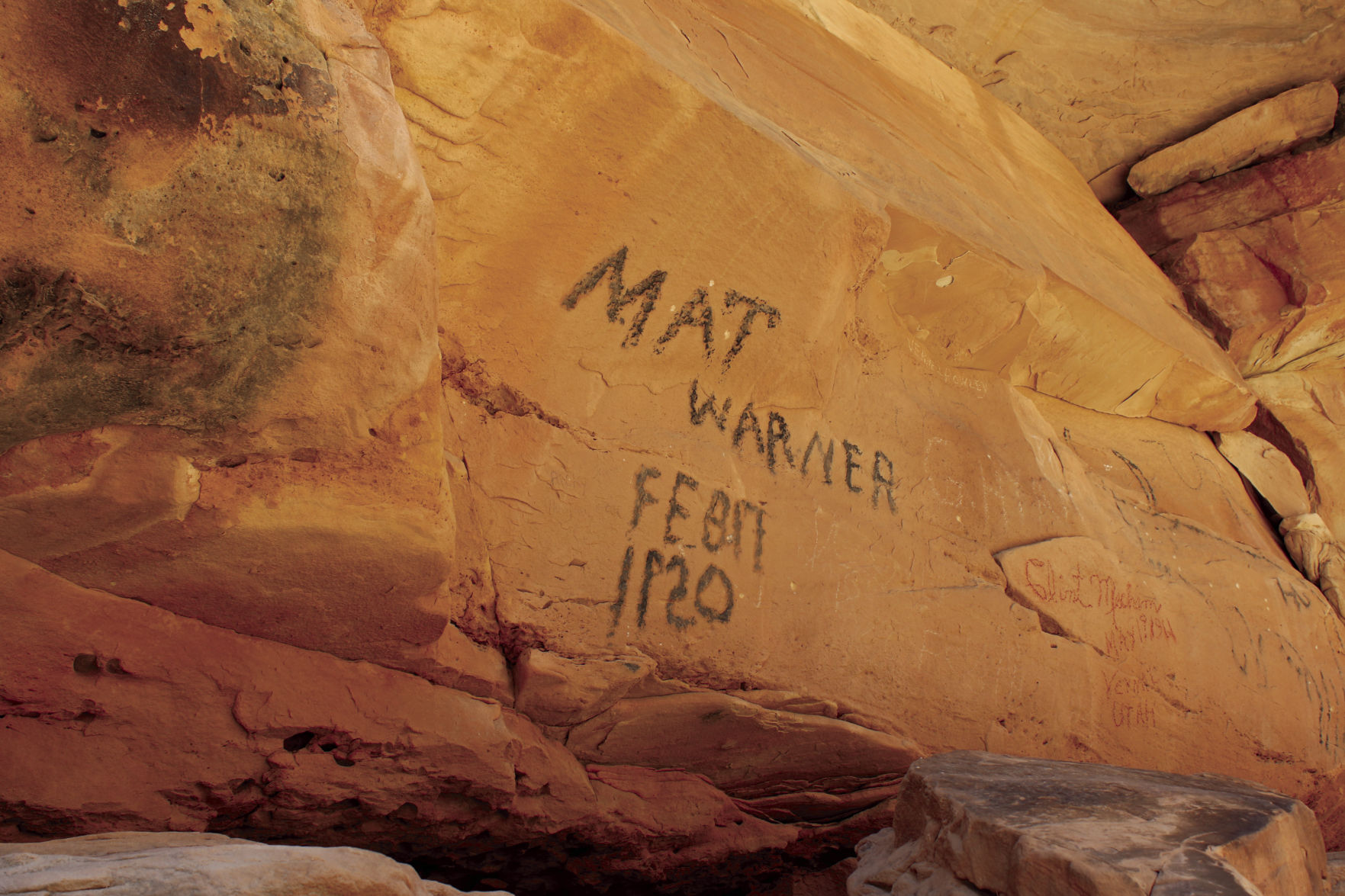

I’d passed by the location on my way to see the spectacular Native American rock art that makes Buckhorn Wash such a draw to tourists. Most passers-by probably miss the names—Lacy said he thinks they were drawn in wagon axle grease—scrawled on a rock wall sitting a bit high, but not a bad climb just off the roadway.

The names were put there Feb. 17, 1920. A drawing of a branded cow was also scraped into the wall. Lacy said he believes a flash flood forced Matt Warner, of local outlaw lore, and his running buddy, Eck Hambrick, clamoring up the sides of the wall, where they no doubt had time on their hands waiting for the waters to subside.

Warner, curiously spelled his first name with one ‘T.’ Hambrick went bigger and bolder with his lettering.

While we examined the names, Lacy shared a story.

“One thing Matt always told his daughter Joyce was that when he was out here a posse was chasing him. They shot his horse and Matt went with that horse as far as he could,” the historian shared, fetching an inexpensive, thin cigar from a package of White Owl. “He rode and rode and rode and the horse fell dead. Matt thought he was going to get arrested or get shot. He saw a lone cottonwood tree.”

Lacy wave toward the cottonwoods by the roadway, as if it could’ve been any of them.

“In this location there is a bunch of cottonwood trees, but where he was at, there was just one lone cottonwood tree. So he grabbed his saddle bags and his rifle and he climbed that one cottonwood tree. He was so much ahead of the posse that was looking for him. He could see a small little cave that you couldn’t see from down below. So he climbed down from that tree and climbed up into the little overhang.

“When he got inside of it, he saw what he thought were little salt sacks inside of it. There were like 30 salt sacks. Anyway, he lay on the floor and that posse finally came by and they searched and searched. There were a lot of rocks around and not many tracks, so finally after hours of them searching, they couldn’t find Matt and they took off.

“Well when Matt finally got to stirring around, he realized it was gold dust in those sacks. Of course, he was on foot. He put a couple of those in his saddlebags and some down his pants and took off. When you are on the run you don’t remember landmarks and details. But he always told his daughter when he came out to the San Rafael area, he was trying to locate that place,” Lacy finished.

The story fits with other tales of lost gold in the San Rafael Swell. Lacy postulated, smoke billowing up from his curled lips, “Maybe they’re (the sacks of gold dust) still there” in that little forgotten cave.

Climbing back into Carter’s truck, we drove back to SR-10 and down through Emery County, passing Castle Dale, Ferron and Emery, the Hunter power plant, the landscape rolling and changing as it does toward Interstate 70.

A VANISHING LANDMARK

Once at the highway, which beckons travelers left or right, east toward Denver or West toward Interstate 15, we instead head straight, under the highway and onto a dirt road.

Meandering along, we encounter what look to be a few old miner’s cabins. We stop at one. There seems to be a coal bed nearby, since some of the smallish rocks scattered among the broken old wooden beams and collapsed walls appear shiny and black like coal.

We are headed toward a rock overhang miles in the distance, along an unmarked route, somewhere near

Cedar Mountain and just north of the border with Capitol Reef National Park.

Lacy is excited to show us a place he believes Butch Cassidy once slept. The drive there seems to double back toward the highway, a desolate landscape that looks more like Death Valley, California than Southeastern Utah.

When we finally get to our destination, amid black boulders of volcanic rock, testament to the area’s furious geological history, we leave the vehicle and walk along a wash to a rock overhand.

There, inscribed in the sandstone is the name Lacy wants us to witness–’Butch Casady’–a misspelled landmark itself on the precipice of vanishing into the ether.

The name is barely visible.

“This is sandstone. Butch had to have darkened these with charcoal from the campfire. He would have taken a rock and knocked off the sand so they would stick out,” Lacy says. “And he spelled Cassidy with an ‘A’ because he hadn’t decided how he wanted to spell ‘Cassidy,’ with an ‘A’ or an ‘I.’”

Lacy said he is saddened about the deterioration of the name, and suspects visitors have attempted to capture the essence by rubbing imprints onto paper.

“It’s a shame, because people have come here and I’m sure have tried to do a rubbing of the signature here and that’s the reason why the things are starting to fall off,” he said. “The ‘H’ you can hardly see. The ‘C’ is in terrible shape. But we’re here to document this before it is completely gone.”

Lacy said he thinks Cassidy was working in nearby Loa and traveled through the area back and forth from work at various times. Lacy tells us about the time he found some old whiskey bottles nearby.

“He camped out here. A few years back, I camped out underneath here and had a dinner with a friend of mine and walking around way out here I found two purple whiskey bottles. I bet they were here when Butch was because they had turned purple,” he said. “Any bottle that was purple had to have been made before 1916. I’ll bet they were from the 1890s. Butch camped out over night. He may have camped here on several occasions.”

Crushing out our White Owl cigars—I couldn’t resist Lacy’s offer of one—we climbed back into Carter’s truck and headed back the way we came, stopping this time at the remains of a mud-brick building not far from the miner’s cabins we’d seen earlier. We had passed right by this building and hadn’t noticed it on the way in. Lacy theorized that it was an old outpost, that perhaps Butch Cassidy himself had greeted the people who occupied it a century before.

Getting onto eastbound I-70, our next stop was Hanksville off SR-24 and the Hollow Mountain gas station on the way to Lake Powell. We stopped for dinner next door and hoped against hope that we would get to where we would camp that night before it got completely dark.

After dinner, we headed down SR-95 toward where the Dirty Devil and Colorado rivers drain into Lake Powell. We pulled off a dirt road in between the two rivers not far from the banks of the depleted lake. It was pitch black, but we managed to set up camp, gaze at the stars, and trade stories by lantern deep into the blistering hot night.

I sweat more than I slept, anxious to get to the “secret hideout” Lacy promised to lead us to in the morning.

THE SECRET HIDEOUT

We all woke early the next day, rain drops thumping against our tents as our alarm clock. For a time it looked like weather would keep us from our ultimate destination. In between down pours we broke down our camp and hoped it would dry enough for us to feel comfortable traveling the rocky back roads deep into Canyonlands National Park from its southern boundaries.

As the rain let up, we ate a spot of breakfast and waited as a new travel companion joined us.

Phil Lyman, a San Juan County commissioner and longtime family friend of Lacy’s, pulled up to where we waited, the sun finally breaking through the wet gray skies. The four of us decide the storm is passing well enough to get going. Sure enough, the skies cleared, our path washed by the morning rain, the desert landscape gleaming from the showers.

Lacy was nervous about whether he would manage to find the unmarked trails that lead to the secret hideout, a place he is sure wanted outlaws Butch Cassidy, Elza Lay and female companion Etta Place spent the winter of 1897.

Lacy shared the story of the secret hideout during an earlier interview.

“They didn’t spend all their time at Robbers Roost. There was a secret hideout. My father found it in 1954. There’s only 16 people who know where this hideout is,” Lacy had previously told me. “There’s people who’ve been there, but they don’t know what it is. Butch and Elza Lay spent the winters of 1896 and 1897 there. There are signatures in the rocks of some other outlaws that were there. But it is 32 miles off the main road and it takes three and a half hours to go those 32 miles.”

Lacy said his father and grandfather found the location when they were building roads for nearby uranium mining operations.

“In 1984, I convinced my dad to go out there, and me, my nephews and my dog, we found it just before dusk, saw those signatures. You could still see where they had taken the box off their buckboard. The tent stakes were still there,” Lacy recalled. “The running iron was still there from when they changed brands on cattle. And the horse collar was still hanging in the cave where they kept the horses. It was totally awesome.”

This is where we were headed. It didn’t quite take three hours, but it was quite the scenic drive, past thinning towers of rock, ultimate pictures of the desert southwest.

Lacy was successful in leading the way, first to where names were scrawled into rock walls, then a short five-mile jaunt to the alleged hideout.

Indeed, there were names, much like the ones from Buckhorn Wash the day before, scrawled in black on a rock outcropping. There was “Ella Butler,” “Mott Butler” and other names, including the date 1897. There was even a hand with a finger pointing north to some forgotten, but no doubt important spot somewhere in the distance. A little white stake was planted in the ground near the rock face; it warned visitors that disturbing historical sites was a crime.

The hideout itself was interesting. It was a natural concave of space in the landscape bounded by shallow caves and walls. A fenced corral and an old freezer containing a length of rope attested to the fact someone more modern has utilized this little divot of land in this wide expanse of nowhere. Inside the shallow caves one could imagine people seeking shelter from the forces of nature. A spring, revealed by a rusty pipe leading from the back of one cave, provided fresh water to anyone who stayed.

Lacy said he had once found a rusty pistol, its handle missing, in the hideout.

We had lunch, Meals Ready to Eat, that Lacy had brought along and enjoyed each other’s company during the meal and the long road back to SR-95 and last night’s campsite.

I slept a bit on our way back. We dropped Lyman off at his truck and he bid farewell. I slept some more on the way back to I-70. I was wide-eyed when we arrived in Green River, stopping for Israel melons and burgers at Ray’s Tavern. Lacy showed us the location where Matt Warner once owned a bar. I found the purple top of an aged whiskey bottle at the location—Lacy said it looked a lot like the bottles he found where Butch “Casady” had signed his name into sandstone.

But the historian wanted to show us one more thing before heading home.

WARNER’S WHOREHOUSE

It sits on a plot of land on Clark Street, in a residential neighborhood in Green River. It’s a dirty white, two-story wood house, its paint pealing off to reveal the weather-stained wood underneath. It is the home where Matt Warner once operated a brothel, Lacy says.

The home is used as storage by its owner these days. The owner lives in a modern home next door.

“If you look up at the side of the house and look at that small window, it’s long, just like the other ones, but it’s narrow,” Lacy says. “This is really common back east. That window goes to the closet. When this was first built there was no electricity. They wanted to be able to go into the closet during the day time and they didn’t want to take in a candle or a kerosene lamp, so they didn’t catch the clothes on fire, so they had a window.”

The glass is original, says the owner, who sees us gazing at the structure and comes out to greet us.

The panes are thicker at the bottom than at the top of the window frames.

Curiously, the building has two front doors, one on the bottom floor and one at the top. Lacy says that was because the working girls—this was before electricity was available—liked to open the second floor door to cool off during hot summer nights.

“I just love this house,” says Lacy, who at one time considered accepting an offer to take possession of the building, moving it up north to make a museum out of it. He declined the offer, regrettably, because to move it, he would have had to chop it into four sections.

After Carter recorded a few new segments with Lacy, we climbed back into the truck for the ride home. Back at the newspaper, I thanked the two men for allowing me—and by consequence, you—to accompany them.

The journey, chasing the ghosts of Butch Cassidy and Matt Warner, was a successful trip through Utah history.