BAD BLOOD

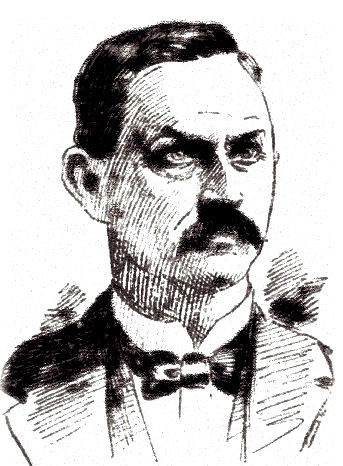

John Wesley Warf, also known as J.W. Warf, was the county attorney for Carbon County for several years, a reign that was filled with nothing but abuse, strife, and questionable antics.

Born July 11, 1867 in Virginia, Warf was the son of a Confederate soldier. He listed his occupation in Virginia as a school teacher. After traveling for many years and claiming to have taught school in at least six different states, Warf arrived in Price, Utah.

Prior to his arrival in Price, Warf claimed to have taught at several schools in Utah, including in Logan, Moab, Molen, and Wellington. On Jan. 1, 1896, Warf began his job as county attorney after being elected to the position in November of the previous year. Warf claimed to have been practicing law since the age of 18. Warf also claimed to be a skilled geologist and had filed many mining claims in the San Rafael area.

Warf positioned himself as a no-nonsense type of a man. He held grudges. Always spoiling for a fight and always ready to be elbow to elbow with the movers and shakers of early Carbon County, Warf was a frequent topic in the local newspapers.

It was his way, or the gun-way.

In mid-May 1898, one year after the infamous Castle Gate Robbery, Warf joined Sheriff Charles W. Allred on a posse intent on capturing Butch Cassidy and Elza Lay. He was joined on this posse by cattlemen George and J.M. Whitmore, Jack Gentry, and cowboy/hired gun turned lawman John “Jack” Watson, among others.

The Texas Ranger, Turned Outlaw, Turned U.S. Marshall

John A. “Jack” Watson was born in November, 1843 in Tennessee. Watson joined and served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War, where he was wounded. This wound caused him to limp for the rest of his life. After the war, Watson became a blacksmith for a time and then joined the famed Texas Rangers. By 1875, Watson was getting itchy feet again and left the Rangers. It was here that he turned to a life of crime.

After several scrapes with the law and many, many nights in the booze bottle, Watson met and befriended Cyrus “Doc” Shores in Kansas. Shores took a liking to the “fallen veteran” and “wild cowboy” in Watson and got him a job bringing in cattle rustlers.

Watson left Kansas and eventually made his way to Colorado, where once again, he had been hitting the bottle. By 1888, Watson was arrested for assault and brought before the Gunnison, Colo. sheriff who was none other than Doc Shores. Shores decided that he was going to once again offer help to the wild cowboy. Shores made Watson a Deputy Sheriff of Gunnison County, Colorado as well as a United States Marshall amid some speculations from the towns folk about Shores’ mental state. Watson, looking for a chance to prove himself, straightened up and began taking down rustlers.

A Cattle Baron In Need–Enter Preston Nutter

In 1896, an old friend of Shores, cattleman Preston Nutter went to Gunnison to ask for help with some rustlers in the Price area. Shores and Nutter had become acquainted during the capture and trial of Alfred Packer, Colorado’s infamous cannibal, in 1874. Nutter had been a financial backer in the gold claim plan, until Chief Ouray had told Nutter to leave the expedition’s soon-to-be-dinner party, thus Nutter avoided being a member of the ill-fated-frozen-food-foray. Shores immediately arranged for Watson to go to Price and work “undercover” to capture the rustlers that were stealing Nutter’s cattle.

In Price, Watson began working as a blacksmith and ending up traveling throughout the county and even living in Nine Mile Canyon for a time. All the while, the undercover lawman was making everyone believe he was just another rough and tumble cowboy. Not liking the looks of the man, and seeing that he had been wounded more than once, the outlaws tended to leave the area when Watson was around.

By 1898, just two years later, Watson was no longer undercover and had been made a full deputy in Carbon County. He was more than willing to chase after the notorious Butch Cassidy and his gang as well as to put an end to the cattle and horse rustling that was rampant in the county.

The Bedroll, Bullet Ridden Death of ‘Butch Cassidy’

The posse with Warf and Watson left Price for Woodside, Utah by train. From there, they met up with others and headed deep into the Book Cliffs on horseback. Led by sometimes outlaw/sometimes lawman C.L. “Gunplay” Maxwell, the posse arrived at the outlaw campsite in the early morning hours of May 13, 1898 and killed two of the four outlaws. It should be noted that according to some of the legends, two of the outlaws were shot to death while they were still slumbering in their bedrolls around the camp fire.

What isn’t in question is that the other two outlaws quickly surrendered peacefully. The posse then trekked several days with their prizes down through the Book Cliffs to the railroad at Thompson Springs, Utah where they took the train into Price. The 13 day round trip was exhausting and all the while they believed that the slowly ripening and bloated outlaws that they had killed were Butch Cassidy and Elza Lay. Gunplay Maxwell played right along and kept asserting that yes, that was who they had killed.

Arriving in Price, the very ripe and zombie-esque bodies were placed on display for the public to come in and view. Some probably even poked the corpses with a stick. The “Butch Cassidy” that was on display didn’t look much like the one that folks in town were familiar with. Using her “lilting” bordello advertising voice, a local prostitute even loudly commented that “this doesn’t look like the Butch Cassidy I know!”

A comment that stopped the crowd cold, and confirmed some of the whispered comments that had been going through the crowd. “Elza Lay” looked exactly like another known outlaw, Johnny Herring, who was much better known and outright hated for rustling the Whitmore’s cattle, claiming it as part of an “inheritance.” It was soon determined that “Elza” was, in fact, Johnny Herring, but the steadfast posse maintained that they had killed Butch Cassidy.

There was a $4,000 reward ($114,225 in today’s money) on Butch Cassidy and only a $500 reward ($14,285) on the man that everyone suspected as the corpse; Joe Walker. It made way more sense to capitalize on the fame and financial rewards to be received by claiming the Butch Cassidy reward.

The Jack-In-The-Box-Pop-Up Corpse

After the multi-day journey to Price and the public viewing of the ripened outlaws followed by a well attended funeral the next day, the bodies were finally buried in cheap wooden boxes outside of the Price Cemetery (actually, just across the cemetery’s fence in the city dump). J.W. Warf sent off to the State of Utah for the reward money on Butch Cassidy. Hearing that there was some confusion about the identity of the body, the body was dug up and examined again. The examination was inconclusive with half of the party (some of which who were entitled to the large reward) declaring it as the body of Butch Cassidy and the other half declaring it as the body of Walker.

The body was reburied. In an effort to determine the true identity of the body and to distribute the correct reward, they sent for the warden of the Wyoming State Penitentiary.

After several days traveling to Price, the warden arrived with records and photos and the body was once again dug up. The warden laughed when he saw the man and claimed that without a shadow of a doubt that it was, in fact, Joe Walker. The dreams of the really big reward immediately vanished.

The $500 reward would be divided up 19 ways for each man on the posse. That amounted to $26.30 ($751.43 today) per person. (Which was still more than an average of two months pay at that time.) Watson was excited for the money as he was broke and was more than ready to leave Utah. By June 8, 1898 the money still had not arrived. Watson asked J.W. Warf to send a telegram to the State of Utah asking for the money, as he wished to return to the East as soon as possible. Warf sent the telegram but in the same day, sent another stating that Watson had sold his interest in the reward money and wouldn’t be needing it. This back-stabbing would cause the relationship between Wharf and Watson to darken less than a week later.

The Good ‘Ole Boy Network Defending A Brutal Attack

With no money forthcoming and needing cash to be able to leave the area, Watson took a job with farmer Charles Marsh and the Price Canal Company. Marsh and Watson walked to the canal that fed Marsh’s farm with the intent to open the headgates and allow the water to flow into the farm. From behind nearby cover, a man named Youngberg appeared and held a shotgun on the men and told them that they would not be opening those headgates. Marsh ignored the man and opened the headgates. Marsh left Watson there on the bank to watch the water.

A wagon pulled up with J.W. Warf and Carbon County founder and fellow attorney Alpha Ballinger. Both men were armed. Ballinger lowered his rifle on Watson, while Warf jumped from the wagon, pulling his revolver stating that the water would not be diverted to Marsh’s farm, as it was needed downstream. Watson remained seated, covered by both Ballinger and Youngberg. Warf walked around the back of Watson and raising the revolver, struck Watson in the head so hard that it cracked his skull and nearly tore off his right ear. Watson fell over and Warf continued to beat him with the revolver and kick him in the stomach and back until Watson fainted.

Watson awoke and sought medical attention. The Price doctor stitched his head and reattached his ear. Surprisingly, Warf and Ballinger were arrested and charged with assault. Warf, using his power as an attorney, requested, and was granted a change of venue. Warf and Ballinger were seen before Helper Justice of the Peace, Thomas Fitch, a known good friend of Warf’s. Justice Fitch dropped all charges against the duo, claiming insufficient evidence of the assault. Warf and Ballinger were free and Watson was angry. After recuperating for several days, Watson began to drink heavily.

The Cowboy Falls

On July 23, 1898, determined to make Warf pay for what he did, Watson went looking for Warf. At 10:00 am, he found Warf in the drugstore next to his offices on Price Main Street. Watson tried to engage Warf in conversation, but when Warf left without saying a word, Watson became even angrier and cursed at Warf. Watson chased Warf into the street shouting “Why won’t you talk to me?”

At 5:45 pm, Warf and several of his friends entered the Senate Saloon. There they found a very drunk Watson at the bar. Reportedly, as Warf turned to leave, Watson shouted “That’s right! Sneak away like the dirty, cowardly “*!##&**” you are!”

Allegedly, Warf had turned to Watson and found that Watson had already drawn his gun. Quickly drawing his own gun, Warf opened fire. The first shot hit Watson in the groin, shattering his hip. Watson went down on all fours and began crawling away from Warf.

Warf’s second shot traveled up Watson’s rectum and came to rest in his rib cage. Yep, good ol’ County Attorney Warf had shot his enemy in the butt. But Warf wasn’t done.

Warf ran from the saloon to the Price Trading Company across the street, where he borrowed a rifle and headed back for the saloon. However, Warf was arrested in the street loading ammo into his newly acquired rifle and was taken to jail.

There is no printed explanation as to why Wharf just didn’t reload his pistol (which should have still had some live rounds in the chambers), other than he really wanted the extra firepower to kill Watson. The gravely injured Watson was placed on the saloon’s pool table, where a doctor tried to perform surgery to save Watson. Watson would die two hours later, still on the pool table. While Watson had family in Tennessee, his family had no money to have his body shipped to them and they requested burial in Price. Watson was buried the next day in the Price City Cemetery.

Warf, facing a charge of homicide and court again, demanded, and was granted another change of venue. Warf would, again, appear before his good friend, Justice Thomas Fitch of Helper. Fitch once again dismissed the case against Warf; citing that “it appeared to him that sufficient justification existed for the act.”

After the haywire Helper “exoneration” by Judge Fitch, it is not clearly stated how the whole thing escalated, but the incidents would be rehashed in court again. By the time the Carbon County Grand Jury met in September of 1898, they too dismissed the two cases against Warf; The State of Utah vs. J.W. Warf, charge of murder and The State of Utah vs. J.W. Warf and A. Ballinger, charge of assault to commit murder. No reason is given for the dismissals.

What really happened between the two men of the law that served on a posse together? Did Watson really sell his share of the reward money or did Warf just say that to gain the extra money for himself? Interestingly enough, according to the records, $26.30 was issued to J. A. Watson for his part in the posse. Did he ever see the money? Or did Warf pocket Watson’s cash? The troubling stories of J.W. Warf and his bizarre behavior don’t end there.

As an ironic side point is that a century later, Walker and Herring’s bodies would be dug up again in the 1980s as a part of the Price City’s Cemetery expansion. The event was semi-quietly documented.