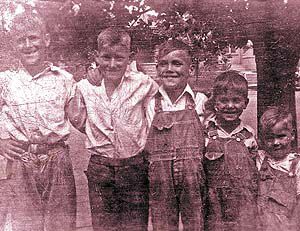

| The Pike Brothers in the early 1930s. Bruce, Bud, Bob, Norman, and Don were all pals. |

There is a flagpole in front of Bob Pike’s house; a very big and a very good flagpole.

There is a deep-seated sense of patriotism among military veterans, and especially among combat veterans. Old soldiers who have faced the cannons fly the flag. It can be counted upon.

Bob Pike is a man who knows the cost of freedom. He and his family have paid the price. He is one of five brothers who served in the armed forces during wartime.

Bruce, Bud, Bob, Norman and Don Pike all grew up in Price, and each walked the valley of the shadow of death for the United States. Four of the boys served during World War II. The youngest brother served in Korea.

Bruce, the oldest son, was killed. A gunner on a Marine Corps torpedo bomber, he was shot down while attacking Japanese ships in Simpson Harbor on the island of Rabaul in January 1944.

The second son, Bud, joined the Army Air Corps in 1939 and retired twenty-two years later as an Air Force Major.

| Bob Pike as he looks today. |

Norman joined the Navy in 1945 just before the end of the war, and Don went into the Army in 1950 at the outbreak of the Korean conflict.

Bob, the middle son, joined the Marines in 1943.

Bob Pike was never a great student. He freely admits it through a wry smile. He dropped out of high school at the age of seventeen.

“I just hung around until I turned eighteen,” he said, “And then I joined the Marine Corps in November 1943.”

He knew his is older brother Bruce was a Marine Corps aviator stationed somewhere out on the blue Pacific, and that influenced Bob’s decision to join the Marines.

Bob trained in San Diego and then was shipped to Camp Pendleton where he was assigned to be a machine-gunner on an amphibious tractor. The big machines were designated LVT, “Landing Vehicle Tracked,” in the jargon of the Marine Corps. Those machines were personnel carriers designed to deliver Marines to the beaches under fire.

| Bruce Pike died in the Pacific while bombing ships over Rubaul. |

An LVT was a big metal box that could float or run on sand and fight through beach obstacles while offering some small measure of protection to the troops inside from small arms fire and shell fragments.

Bob shipped overseas on July 31, 1944 with the 8th Amtrak Battalion of the First Marine Division. He was sent to the Russell Islands near Guadalcanal. In mid-September 1944, Bob landed with the First Marine Division on the island of Peleliu. Peleliu is a small coral archipelago southeast of the Philippine Islands. Peleliu harbored a Japanese airfield that threatened General MacArthur’s planned invasion of the Philippines.

The battle for Peleliu has never received the attention that Iwo Jima and Okinawa have received over the years, but like the battle for Tarawa, it was one of the most savage of the fights in the Pacific. A well-entrenched Japanese garrison of 13,000 men defended the beaches. The Americans suffered 8,769 casualties while capturing Peleliu and the fighting lasted for weeks.

Bob Pike and his amphibious track crew were there for the full fight. They would take a load of Marines into the battle and then load the track with wounded to take back to the beach for evacuation. They would then pick up another load of fresh troops and go back into the fight.

| Bob Pike in the South Pacifice in 1945 |

“We just went back and forth, and back and forth,” Bob says with a painful smile.

When pressed, he said he was never wounded.

“We were rescuing a wounded guy who had lost an arm, and as we carried him back, a Jap Nambu machine-gun opened up on us.” He indicated with his hand that bullets hit so close to him they kicked sand on his uniform.

After the battle of Peleliu, The First Marine Division was sent back to the Russell Islands to refit and prepare for their next assignment. While there, Bob had the honor of taking famous war correspondent Ernie Pile ashore on the island of Ishi Jima. Pile rode as a passenger in Bob’s vehicle.

“He was a great guy,” Bob remembers, “No pretensions, just one of the guys.”

Ernie Pile was killed six weeks later during the battle of Okinawa.

Bob Pike and the First Marine Division went ashore on Okinawa on April 1, 1945. Okinawa was the last, largest, and most costly of the amphibious invasions of the Pacific war. The island is only about 400 miles from the Japanese home islands and the Empire of the Rising Sun fought savagely to keep it.

Most people don’t know it, but more people died during the fighting for Okinawa than died in both atomic bomb blasts at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Japanese army lost at least 107,000, and possibly as many as 130,000 men. Civilian casualties among the native Okinawan population might have been as high as 142,000. Many civilians fought with the Japanese Army and thousands of others committed suicide. Sadly, many more were killed accidentally in the crossfire between the two armies.

| Bob Pike was Utah school bus driver of the year 1989 – 1990 |

The Americans lost 12,000 killed and more than 38,000 wounded. Our side lost 34 ships and 763 aircraft. The Japanese lost 16 warships and 7,830 aircraft, many of them used as kamikazes. The battle lasted for 82 days and then mop-up operations continued until after the end of the war in early September.

Bob Pike went ashore on April 1st, the first day of the battle, and he was still there when the war ended over five months later. “I was on the northern tip of Okinawa when they dropped the bomb,” he says. “About as close to Japan as any other American, I guess.”

After the first few weeks on Okinawa, when all of the troops were ashore and the battle had settled into a slugging match between the opposing forces, Corporal Pike and his track crew took their armored vehicle into Naha, the Capital City of Okinawa. “We just went in there to snoop around,” he said with a smile, “And we sure got chewed out by our officers when we got back.” Naha was still officially in the hands of the Japanese. “We didn’t see any,” he said. “Maybe we were lucky.”

When asked if he agreed with President Truman’s decision to drop the atomic bomb, Bob said it was the right thing to do. “We were preparing to invade the home islands,” he said. “It would have cost too much.”

He believes that dropping the bomb actually saved many thousands of lives. Judging from the savagery of the battle for Okinawa, Bob is probably right.

| LVT: Landing Vehicle Tracked like the one Bob Pike rode in during the war. |

After the war, Bob settled into civilian life. In 1948 he married Charlotte Winiski and they made a home and a life together. It was a good marriage, and they recently celebrated their fifty-seventh wedding anniversary. They have one son, Robert Bruce, and two grandsons, Cody and Danny.

Bob worked for Wycoff in Salt Lake City for a while, and then returned to Price where he sold cars at Mountain View Motors for many years. In 1960 he began driving school bus as a second job, and he drove bus for 41 years before retiring in 2001. He was much loved and much appreciated by the students who rode his busses, and he was recognized as the Utah State School Bus Driver of the year for the 1989 – 1990 school year.

In 2002, Carbon High School honored Bob Pike and three other War veterans with honorary High School Diplomas. Each of the men had quit high school to enter the armed forces and defend the nation during World War II. It was a touching tribute. Bob smiles when he thinks back on it. “It took me sixty years to graduate from high school,” he says with a big grin, “But I finally made it.”

As a community and a nation, we will forever be in the debt of men like Bob Pike. When you see him on the street, be sure to shake his hand and thank him for his service. And remember, Friday, November 11 is Veterans Day.