| Many cultural treasures lie inside the Range Creek area. |

It was called one of the most significant finds in North America in the past 50 years. Nestled in the heart of Central Utah in Range Creek Canyon were the remains of a lost civilization that once thrived in the American Southwest.

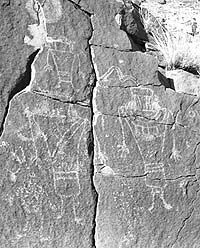

For 500 years, the Fremont Indians lived in parts of the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau as hunters, gatherers and farmers. They left detailed art and symbols on the stone faces of canyons they inhabited and stored their grain high on cliff walls in well-built granaries that still survive. Then, 800 years ago, the Fremont seemingly disappeared.

Today, University of Utah archeologists are surveying an entire canyon of some 2,000 untouched Fremont Indian sites. Airing Monday, Nov. 21 at 8 p.m., KUED’s new documentary, “Secrets of the Lost Canyon,” looks at the issues surrounding the discovery and preservation of this incredible archeological find.

Protected for half a century by a Utah ranching family who knew they were living in the land of the ancients, the sites form an unexplored gold mine of historic artifacts. Those artifacts, which suggest that communities of up to 600 people once dwelled there, include 70 pit-house villages and grain-storage sites, many of them accessible only by rappelling.

Archeologist Duncan Metcalf of the Utah Museum of Natural History claims in his 30 years of field work to have found only six or eight sites which have escaped the presence of modern man.

“We’re at about 295 sites at the moment in this portion of Range Creek Canyon,” says Metcalf, who is the lead archeologist on the Range Creek project, at one point in the documentary, “and those within the confines of the gate are almost 100 percent pristine.” Utah State Archeologist Kevin Jones calls the concentration of sites and their pristine status “a national, perhaps international, treasure.”

The sites have endured since the only access to the remote canyon was through ranch gates controlled by the Wilcox family since the early 1950s. As soon as the State of Utah announced the purchase of the land from the family in July 2004, a race against time was triggered. Local, national and international media picked up the story, quickly spreading the word about the historic cultural find. Illegal collectors were soon targeting the site for “pot- hunting raids” to strip artifacts for resale on a lucrative black market.

Simultaneously, Native American groups protested the state’s handling of a landscape that several tribes considered ancestral burial sites. Native American groups from the Goshute and Ute tribes joined the State Office of Indian Affairs in demanding a role in handling what one tribal leader called “the graves of my family.” Natural resource, wildlife, museum, history and archeology managers representing competing interests also wanted a place at the table. The state of Utah suddenly found itself at center stage of a sharp debate over how to manage Range Creek Canyon.

The KUED production team for the production was led by Ken Verdoia and Nancy Green. While Verdoia kept his feet on the ground tracking the competing interests at play in Range Creek, Green rappelled with archeologists into the most remote Fremont sites, located on sheer cliff faces high above the canyon floor. Gary Turnier chronicled the beauty of the untouched location as the project’s Director of Photography.

Lost Canyon captures the first glimpses of the prehistoric sites containing undamaged rock art, housing and artifacts in wilderness-like settings. It also highlights the colorful and determined family that protected the landscape for 50 years as well as the furor created when state officials sought to act quickly to claim the location, and begin cataloging artifacts.

The documentary also looks at the future of the Range Creek site. Should it be public land opened to hikers, photographers, archeologists, hunters and backpackers — or should it be transferred to Native American jurisdiction? Should the artifacts be pulled from the ground and placed in museums?

What was once an overlooked piece of private property wedged in the tough landscape of central Utah now commands our attention. “In Range Creek, we discover an opportunity to better understand those who lived in this land three and four times longer than the history of the state and nation that now surround its remains,” says Verdoia. “And, perhaps, of even greater importance, we face an opportunity to understand our own relationship with the timeless nature of our unique landscape.”