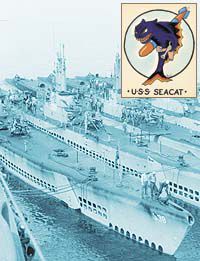

| The USS Sea Cat (399) sits along side sister submarines Segundo, Blenny, Blower, Blueback and Charr in the harbor at Guam in 1945 just after the war ended. |

When Norman Patterson received the call from Uncle Sam in 1942 to report to Fort Douglas, he thought his high school and mine works days were over for awhile.

But after reporting to the Salt Lake facility he was told that if he decided to go in the Navy, he could go back to his home town of Sunnyside and finish school.

So that’s what he did, and rather than end up on the front lines somewhere, he ended up fixing and then manning a United States submarine.

“The thing was it was never too exciting,” he said. “For the most part I just rode around in one for a couple of months.”

But Patterson’s trip to the underwater realm started in a seemingly unlikely place by todays standards; Faragut, Idaho.

But if one looks closely at this location, this place is a very good place for submarine training, at least as to how it was done in the 1940’s. The Faragut Naval Training Station sat right on Pend Oreille Lake, one of the five deepest lakes in the United States. The lake is also large: 43 miles long and six miles wide.

During training there Patterson learned the skills that it would take to maintain electrical systems on submarines.

“There were a lot of guys from Carbon County there,” he states. “When we headed up there from Fort Douglas there were 10 or 12 people from our area. We were all in Company 521 for basic training.”

| Norm Patterson during basic at Faragut Naval Training Station. |

As with many Navy personnel, after he was done with electrical school, he was sent to Treasure Island in San Francisco, and then onto Pearl Harbor.

“I spend quite a few months there repairing damaged boats,” he says. “Some of those submarines would come back to port with half their conning towers missing, bent periscopes, all kinds of damage. I don’t know how they got some of them back for repairs.”

Hawaii at the time was an armed camp that was the stepping off place for the war effort against the Japanese in the Pacific Ocean.

“I would go on leave and all you would see is a sea of white walking up and down the streets,” he explains. “The white Navy uniforms were everywhere.”

Of course other branches of the armed forces were present there as well. The Marines and the Army also had a big presence as well. That made for some real service rivalry and often led to fights in bars and other places.

“There was this guy from Helper that I knew that was serving on the North Carolina (battleship)” says Patterson. “One day I went to town with him and he started to drink a little too much. He started bragging how the North Carolina was winning the war by itself. I left before he got to bragging too much.”

Patterson was probably lucky because a couple of days later he saw the guy and he incurred two black eyes in the ensuing melee.

In 1943 Patterson was sent back to the United States to work on electric torpedoes in New London, Conn. Those torpedoe engines were driven by batteries and were more dependable than the ones the Navy had been using that were driven by an alcohol burning motor.

“I think the biggest problem with the old torpedoes were that the guys in the boats would take the alcohol out of them to drink and so when they were put in the tubes they had nothing to run on,” says Patterson.

| Patterson walking with a buddy while taking leave in Hawaii. |

But his days of being on land were numbered. Soon the naval production of submarines was going full steam and unbeknownst to him on February 21, 1944 his soon to be ride under the sea was launched at Portsmouth Naval Yard in Maine. The SS-399 Sea Cat was a Balao class of submarine and had been completed in only a few months after it was begun. This was done with newly advanced welding technology that made the new boats stronger and faster to build. After sea trials it was ready to sail off to war and Patterson, who was now stationed at Mare Island in northern California helping to put old ships out of commission, was soon to be assigned to the new submarine.

“When we left San Francisco the water was very rough, but when we dived it smoothed right out,” says Patterson. “You could tell we were diving because of the angle, but once we reached cruising depth, it leveled off.”

Patterson said other than the fact the space was very tight, most of the time under the water it was like sitting in his living room because you couldn’t tell where you were. His duties on board included taking care of electrical systems, particularly electrical panels.

On the boat he also had a Carbon County friend with him. Ken Anderson, who Patterson says lives in Provo now, but was from Helper at the time, was with him on that trip toward the submarines ultimate destination of China.

“I wish I still had some of my photos and stuff from that time, but I left it all on the submarine tender where we lived when we off the boat,” he says. “When I came back the tender and my stuff was gone.”

The reason he left stuff behind is because there was little room in World War II model submarines for anything but fuel, equipment, weapons and the men who ran them. Tight quarters is actually an understatement according to Patterson.

“We had to hot bunk,” he said, referring to the fact that there weren’t enough beds on the boat for everyone to have their own. “One guy would finish his shift and then another would go on. The guy who just came off would take his bed.”

| Norm Patterson in more recent times. |

The Sea Cat would travel under the water during the day under battery power and then would surface at night so the diesel engines could recharge the batteries for the next day. This was done so that enemy ships and aircraft could not attack the submarine.

“It was great when we surfaced at night, because they would let a few of us up on the deck at a time to get some fresh air,” he said. “But when the weather was bad we often wouldn’t surface and the air would get terrible down there.”

It wasn’t that it only stank, but that the oxygen level actually would drop.

“You could lay a cigarette down and it would die out because there wasn’t enough air to keep it going,” he says.

As the boat headed toward China it took a day in port in American Samoa. He had a chance to get off it for a few hours but then the trip sped on. As they headed north he wondered what they were doing and he was told that they were taking pictures of islands through the periscope as they made their way toward where the war was raging.

In the Navy at that time a sailor could accumulate points for certain duties and when the time came personnel could opt out of the active service and go home. When the boat stopped in Guam both Patterson and Anderson realized they had enough points to go home. They took a surface ship back to the west coast and were soon discharged.

Patterson however, stayed in the Naval Reserve for six years and in 1952 he got completely out of the service. During that time he had returned to Carbon County and worked for the Denver Rio Grande Railroad. He later went to work for the postal service and retired from there in 1986.

| This United States Navy photo shows how tight the quarters were in a World War II submarine, with bunks for men to sleep everywhere. While this photo does not portray an exact duplicate of the conditions Patterson and other sailors endured, he says that he did bunk in the area where the torpedoes were stored. Because of a shortage of sleeping space sailors did what is known as “hot bunk” or take a bunk from a sailor who was leaving to go on duty. |

“I never saw any combat or was shot at during the war,” says Patterson. “And I got out of the reserve just a little less than a year before Korea heated up. Many of those guys in the reserve unit ended up going to that war as well.”

The Sea Cat went on to the war and was involved in a number of actions before the war was over. It also served during the Korean War, and was used by the Navy for various duties up until 1968 when it was decommissioned and sold for scrap.

Patterson is humble about his war contribution, but as most military people know, it takes a lot of people maintaining and repairing equipment and providing logistics for a war effort to succeed.

A few years ago Patterson returned to Hawaii and was amazed at the changes.

“You know there is nothing left of what was there in the 1940’s,” he says. “It doesn’t look like the same place.”

But as everyone knows, without people like Patterson who fought the war in his own quiet way, it probably wouldn’t even be a state.