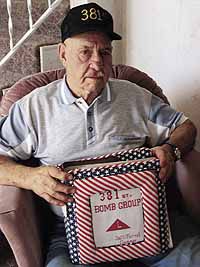

| Dale Jensen holds a book that his wife made him to hold the memories of his wartime experiences. |

For those who have fought in a war, often the little things bring back memories… a taste, an odor, a sound.

For Fred Dale Jensen, it’s the sound of footsteps.

“I remember laying there in my bunk in the barracks and listening for that sergeant to come down the path to wake us up,” says the ex-Army Air Corp gunner as he sat on the sofa in his house in Wellington. “Sometimes he would pass the barracks by and then after laying awake all night wondering whether we would have a mission in the morning, I could go to sleep.”

But there was also the other side of it.

“If he came it was as if he was saying “You gotta go die so wake up.”

Those footsteps he listened for came over 60 years ago when Jensen was stationed in Ridgewell, England. The American 8th Air Force was running daylight bombing runs into Germany, France and other European destinations that were occupied by the Nazis and Jensen was a key part of his B-17 crew that flew on such missions.

Originally born in Cleveland, when the war was raging in the early 1940’s he was working in the aircraft industry for Douglas in the Los Angeles, Calif. area when he was drafted into the service.

“It was a good job and I was a machinist,” he says. “I actually made parts for the B-17 assembly line, but I never did figure out where those parts were in the planes even with all the time I spent in them.”

He and another guy from the Castle Valley area both worked at the plant and told management they wanted to take a few days off to go deer hunting in Utah. Their boss told them they couldn’t take off because the operation had to run seven days a week to supply the planes that were needed for the war. He also told them that as long as they were employed at the factory they wouldn’t be drafted.

Neither of them were sure that was the truth, but they found out it was true when they left to go back home and then were drafted when they returned.

He later learned that his buddy that he had hunted deer with was killed in air combat two weeks after he arrived in England.

| The cover from the book Dale received from the 381st hovers. |

The next thing Jensen knew he was at Keesler Field near Biloxi, Miss. in basic training. That was in February of 1943. After a few weeks there he was sent to Harlingen, Texas for gunnery school, where he was turned into a turret gunner… the belly turret gunner.

“When I graduated from gunnery school we were standing in formation and the officer who was speaking told us to look at the man in front of us, the man to the right of us and the man to the left of us,” he says with sadness in his eyes. “He then told us that if one of us was alive at the end of our 30 mission assignment in England, the other three would be dead.”

When Jensen left Texas he knew the survival rate for air crews over Europe was only 25 percent, but that was actually much better than the 10 percent rate that was realistic in the earlier years of the American technique of daylight bombing over Germany.

Because the belly gunner was also assigned to handle mechanical problems in flight, Jensen was sent back to Keesler Field to go to mechanics school.

“So we were considered engineers,” he says.

That only gave him a few weeks respite before going to England, which passed quickly. He worried and was scared and when he went on his first mission he wondered what it would be like.

“Our first mission was so easy,” he said. “We flew across the English channel and were supposed to bomb a target there but the mission got scrubbed so we came back.”

Jensen says that on that flight the plane not only had 1000 lb. bombs in the bomb bay of the aircraft, but also had wing racks with 1000 lb. bombs under the wings. Before landing the pilot decided he didn’t want to land with armed bombs hanging out so he dropped them in the channel before they reached land.

That was in February of 1944 and he had a long way to go before the next 29 missions were over. He was often in a replacement crew, one that filled in when other crew members were missing. In doing so he often was in the lead plane in a bombing formation. In that plane was the bombardier that made the decision to drop bombs for an entire group.

Jensen was assigned to the 381st which was known by its insignia a “Bat out of Hell.”

He remembers many incidents of his days in those big armored planes. Some memories are comical, most others bring back thoughts of pure terror.

| The symbol of his group, a “Bat out of Hell.” |

“One of the problems with being a belly gunner is because of the gun sight in the turret there wasn’t enough room for the gunner to wear a parachute,” says Jensen. “So I learned to manually open the canopy (it was hydraulic, but he practiced with the manual crank so if the power was out) and put on my parachute in less than 20 seconds. I thought that could save my life.”

But he found out that things happen so quickly in air combat that the chances of him saving himself in an emergency was remote.

“We had completed a bombing run and our pilot got vertigo and we went into a spin. The guys in the cabin were pinned against the side of the fuselage and couldn’t move. In my position I didn’t even realize what had happened until it was over. We had gone from an altitude of 28,000 feet to 13,000 feet in only a few seconds. I could never have gotten out in time.”

He said the worst mission he went on occurred during a raid over Germany on May 24, 1944.

“We lost so many planes that day it was unbelievable,” he states as he looks off into the distance. “We shared the barracks with an another air crew and they never came back.”

However, years later he learned from one of his fellow crew members that one of the guys from that crew had survived and been captured, even though Jensen’s flight crew never saw one parachute come out of the plane as it spun toward the ground.

“Years after the war this other guy from our crew was passing through this small town and remembered that one of those lost souls had come from that town. He decided to look up the family but when he gave the name to the motel clerk where he was staying they said the only person they knew by that name in the town delivered the mail to the motel every day,” said Jensen with a smile on his face. “He waited around and when the mailman showed up it turned out to be that red headed fell that we all thought was dead.”

The man told Jensen’s friend that he had been burned badly but had been able to get out. In a prisoner exchange he was sent back to the states to recover, but he had no idea what every happened to the rest of the crew on his plane.

It was typical of war. An airman would get to know someone and the next thing they knew the person was missing in action. Seldom did they find out what happened.

| Dale Jensen in 1944. |

Camaraderie among air crews, guys in a gun turret on a ship or men in a foxhole on the ground is typical of war time. Many who survive combat say they were never as close to anyone in their lives as they were to their buddies with whom they faced death. There were the serious moments and then there were the jokes.

“We had one guy on our crew who was born in Germany and then moved to the States when he was a kid,” says Jensen with a smile on his face. “He used to tease us that if he got shot down he wouldn’t be a prisoner because his family that was still in Germany would take care of him. He said he would sign a note to tell our captors to take good care of us.”

He did get to go off base once in awhile and even made it to London a couple of times. Once, one of the crew members hijacked a farmers cow and somehow got it on the train with them and took it back to the base. It was quite a group of guys he says. They came from all over the country and after the war they went into professions that ranged from being a lawyer at the White House to the pilot who became a cabinet maker.

Jensen felt he and his flight crew had a guardian angel watching out for them. Every one returned to the states after their missions had been flown. Only one was wounded in action. It helped that they all took care of each other too.

Jensen and another crewman had a chance to end their stay in England a little earlier than the others because the decided to volunteer for a mission as replacement on a crew that needed them. But the officer in charge told them they couldn’t go because they had seen to many flights in a row and needed a few days rest. They were anxious to go home, but had they been allowed to climb on board, they would have probably never gone home. That flight was shot down with all hands lost during the mission.

Being a belly turret gunner brought Jensen a lot of respect from his fellow crewmen. For most people it was the last place they would want to be in a plane where German fighters and enemy flak continually bombarded the aircraft. In fact the navigator told him once that if they had made him get down in that round ball of glass and steel he would have gone AWOL instead.

After Jensen left England to come home, he never thought he would get to fly in another B-17 in his life. He also wasn’t sure he would want to. But by the chances of the weather he did get one more flight 40 years later.

| Jensen when he graduated from gunnery school in Texas. |

One the last day of May in 1994 a B-17 owned by the Confederate Air Force was making its way from Texas to Ogden for an air show when it ran into some towering thunderstorms. The air crew decided it was best to land at the Carbon County Airport and last out the storm.

Word came to Jensen that the plane was there so he and his family rushed out to see it. The plane was like the one he had flown in so many times and it even had his air groups markings on it. Jensen encountered the pilot who was removing luggage from the plane for an overnight stay and when he told the airship’s captain the story, he invited Jensen to fly to Ogden with them the next day. Jensen decide to go, but not without trepidation at first.

“That plane was a lot noisier than I remembered them being,” he said. “I guess with our intercom earphones on and being so busy when we were flying missions I didn’t notice.”

Jensen’s family drove to Ogden and picked him up. He and they will never forget that last flight he took. And in a way he took for all the others on his crew that came back to the United States from the biggest war man has ever known.

“Almost everyone that was on the crew is gone now,” he said as he looked out the window of his house. “Besides me there is only one guy left and he lives in Ohio. He lost his wife last year. I need to call him and make sure he is okay.”

Still being part of that air crew, still watching for that guardian angel.