When Clarence Pilling found some figurines at the back of a cave on a ranch he owned in Range Creek in 1950 little did he realize the fire storm that other artifacts that existing in the canyon would cause over 50 years later.

Pilling, who also owned a motel in the Price area, later displayed these early clay figures in a non-descript glass showcase so that visitors could see them. Today such a find would make national news, even the international media would jump on it.

“Up until that time,” he later said, “I had found only corn cobs, and broken pottery, nothing of much permanent interest until I peered into this cave, climbed over a pile of broken rock, looked at a shelf near the back of the cave and saw the most perfect 11 figurines you can imagine.”

The “corn cobs” and “broken pottery” he passed over at the time, things that had “nothing of permanent interest” today commands great respect from archeologists. Those are many of the same things that remain today, very much like they were in 1950 and as of the beginning of this month the world has put this little canyon in it’s sites.

At the time of Pilling’s discovery there was some publicity about the discovery. In 1953, after the figurines spent some time at Harvard University, a book was published that was called Clay Figurines of the American Southwest. After that the excitement kind of died away until 1961 when Pilling donated them to the then new Carbon College Prehistoric Museum. There they have stayed most of the ensuing years.

But while they remain locked up in a case displayed on the east wall of the museum, their partners in history, the remaining artifacts hidden in Range Creek, have remained hidden from most of the world until lately.

The change in status came when the land in the area, owned for 50 years by the Wilcox family was sold to Trust for Public Land (TPL) in December of 2001.

The purchase of the property by the TPL brought about some private concerns by various county and local officials who were concerned about what the action meant. The TPL is often involved in buying property and placing conservation easements on it. TPL holds the property or gets other federal and state agencies to buy and administer the land. That is not always a bad thing. But in some cases, the easements restrict the prior uses and often affect future use.

Conservation easements are generally set up to protect specified lands “in perpetuity.” The provision means that, even when the land is sold to another individual, business or government agency, the easement still holds and cannot be violated.

| Waldo Wilcox as he was interviewed in Range Creek by the media. |

In some parts of the country, a movement has been started to make it so easements have an ending point in time, such as the death of the owner or when land is sold, but groups in favor of the easements argue that the reason for them is to protect the land in the long term and not only during one caretaker’s life-span or ownership.

In 2003, the United States Congress approved allocating federal money to help Utah purchase the land from the TPL. Combined with funds from the Utah Quality Growth Commission and several sporting groups, the land was transferred to state ownership. At that point a working committee consisting of a number of county, state and federal agencies was set up to study what to include in a management plan for the site.

Initially, the emphasis was on the wildlife and fisheries in the area, and to a large extent it still is. The area is full of wild turkeys, hawks, eagles, cougars, elk and deer. The stream could also become an important fishery. The conservation easement will be managed by the Utah State Division of Wildlife Resources (DWR).

But the discovery by state archeologists of what is estimated to be 2,000 to 5,000 undisturbed sites has fueled the imagination of people across the country and consequently led to the large influx of outside news sources seeking information.

Now it is up to the state of Utah to protect the treasures that remain, yet they also have to satisfy the fact that it is, afterall, public land purchased for public use, particularly for sportsmen. The fact is everyone is concerned.

“I worry that the place will be full of beer cans before too long,” Waldo Wilcox told some representatives of the media during the tour three weeks ago.

Almost everyone is worried in the same way. That’s why a number of agencies are working together to create a management plan for the area which is due out in January of 2005. That plan is being developed by representatives of the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, the Utah Division of Forestry, Fire and State Lands, the Utah Department of Agriculture and Food, the Institutional Trust Lands Administration, the State Historic Preservation Office, the Bureau of Land Management, Carbon County, Emery County, the Utah Museum of Natural History, the University of Utah, Sportsmen for Fish and Wildlife, as well as some local private landowners. The plan will receive public review through the DWR’s Regional Advisory Council process and will ultimately be approved by Utah’s Wildlife Board.

“We are working on a management plan as quickly as possible,” said Derris Jones, regional supervisor for the DWR on Wednesday morning. “The governor has told us we need to get a temporary plan together right away. In fact there is a meeting with many of the stakeholders in this afternoon.”

However for some the process will not be completed soon enough, and for others it may be coming too fast.

Protection of what remains, which is substantial due to the fact that Wilcox kept almost everyone out, is paramount to preserving the integrity of the sites.

“I know there were stories that I kept people off the property with a shotgun but it never did come out of the house to be used,” Wilcox told KUER radio about two weeks ago. But for some who want to keep the land the way it is, except for scientific study, they see the shotgun” approach as the way to do it.

“We are trying not to get to conservative about protecting the sites too quickly,” says Jones. “Obviously the land was bought for public access and we have violated that process if we shut it off. It’s a very fine line to follow.”

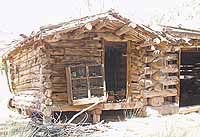

| Looking at pieces of artifacts in Range Creek. How to keep access and still let people see the canyon is the question. |

Already the DWR has instituted a live in caretaker on the land and officers from BLM, DWR and the Emery County Sheriff’s Department are patrolling it constantly.

“Everyone needs to remember there are a lot of people constantly in that canyon that care about it too,” stated Jones. “Not only do we have a caretaker but there are a number of students and archeologists from the University of Utah and the College of Eastern Utah. There are a lot of people watching what is going on.”

Presently there is a gate that blocks access from lower Horse Canyon, but there has been talk of moving the gate down the canyon even farther to make it a longer walk for the public to get into the land.

In actuality officials admitted on media day that they weren’t ready for the onslaught, but once the story leaked out they had no alternative but to show it off. Certainly no responsible citizen wants to see the area destroyed or looted, although in the three years since the land was sold to the state some of that has happened. But open public land advocates also are concerned about being blocked from an area their tax dollars paid for. They are particularly concerned about the role of the BLM because they have a lot more land in the area to be concerned with than the state. One of those is Carbon County resident Alan Peterson, a stringent open public land supporter.

“…the Wilcox acquisition land is pretty well secured, protected and patrolled by county, state and federal employees,” says Peterson. “But there lies the dilemma for the BLM. How do they keep the public out of the public lands in and around Range Creek?”

Peterson says the BLM may use road closures to keep people out of the lands and he sees that as a very poor idea to even have under consideration.

“If they do that they will be making a knee-jerk reaction in order to prove to somebody that they are doing something about nothing,” he states. “Every other knee-jerk reaction I’ve seen the BLM make not only fails to solve the problem but actually creates a few new problems. They just seem to follow the axiom ‘when in doubt, close the roads'”

A complicated and convoluted problem faces everyone who loves canyons such as Range Creek and the lands around it that may also be rich with artifacts. Jones says the interim management plan will address many of the issues. He also said that despite the mid-winter date for a total permanent plan to be released, he thinks it will take a little longer than that to get everyone together and on the same page.

In a recent interview with the Sun Advocate about Nine Mile Canyon, CEU Museum co-director Pam Miller worried that as more and more people come to visit the “worlds longest art gallery” it might get “loved to death.”

Could the same thing happen to Range Creek as well? Only time will tell.