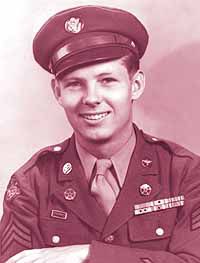

| Cline before being shipped to the Philippines. |

The beginning of his story is not that different from many who came of age in the late 1930’s. As a young man from Cedar Rapids, Neb. Buss Cline planned a life that he hoped would lead to peace and security. He graduated from Cedar Rapids High School, then went on to two years of college at Grand Island Business College, after working for a year in a grocery store to supplement the scholarship he received to attend the school.

Upon graduation at the age of 21, he could see the storm clouds gathering in the East and in the West, and it wasn’t a Nebraska twister. It was war.

It was at that point he made a decision to join the Army. It was November of 1940, and America was ill prepared to fight a war. His education helped him into administrative positions within the service, and soon he found himself volunteering for Army Air Corp duty, but not for flying. He became an interviewer of young men who wanted to be air cadets all over the upper midwest, stationed fairly close to home in Omaha. But an officer he knew asked him to transfer to a different unit, one that was stationed in a town a thousand miles away. It was a unit called the “Footlocker fifth” based in Salt Lake City. That transfer would prove to be fateful.

While stationed in Salt Lake he was introduced to a girl who would eventually come to be his bride, but what he didn’t know they was that it would be a long five years before that happened. Only a short time later he was shipped off to the Philippine Islands as the buildup to a war everyone knew was coming, but just didn’t know when would happen, began.

He ended up on the island of Mindinao 15 to 20 miles inland on the north shore in a support force that was building an airfield for B-17 bombers. In fact the airbase was called the Del Monte Airbase, because it was just across the national highway from one of the largest Del Monte pineapple plantations in the world.

While there, and before the Japanese began to attack and invade the islands, he acted as a company clerk. He was often asked to go into town to buy stuff for the company and when he did he found a family owned cafe he really like to go to.

“I love to eat chicken,” says Cline.” Many people go to restaurants and when they have to wait very long they ask if the chef had to go out and kill the cow. Well in the case of this place, when you ordered chicken that is exactly what they had to do before they could prepare it for you.”

He made many friends among the local tribesman and says he found Philippinos to kind and gentle people and he loved them.

Then came Pearl Harbor, but for Cline that was a far away occurrence as that same day bombs began to fall from the air on Mindinao. He found himself in the middle of an Army that was trapped and had little to fight with.

“The weapons were all old,” he says. “At that time the only thing we had of any power was one water cooled 30 caliber machine gun. Our rifles were World War I Enfields and when I looked through the one that they issued me it looked as dirty as a stove pipe even after it was cleaned.”

Japanese planes flew over all the time and one day all the guys around him began firing their rifles at a plane as it flew over. One of the officers came over and told them to stop because he recognized the aircraft as an American P-40. When the pilot landed he came over to the group, laughing and said “It’s going to be a long war boys if you shoot like that. Everything you threw up was way behind me.”

| Cline while in one of the prison camps. |

Soon after the personnel on the base scattered and Cline was moved to the Maramagi Forest at the interior of the island. Later they were moved back to the coast and down to Davao.

“One day I was writing a letter to my either my parents or Beth (his future wife) and the Japanese attacked,” says Cline. “I was in the mess tent and shells started flying through the canvas so I ran outside and jumped in a foxhole and landed right on top of a Phillipino who was also trying to hide out. That was a shock.”

But that was not as much of a shock as what he and others faced when General Jonathan Wainwright surrendered all the forces on Corrigidor and along with them all American forces in the Philippines. He and a group of soldiers headed off to surrender to a Japanese column but were intercepted by another before they could get there.”

“The Japanese soldiers were brutal,” he says with a far away look in his eyes. “I learned from the beginning to stay away from them as much as possible. There were a lot of guys that would get right in their face and those were the people that got the worst of it.”

Soon his small group of a couple of dozen men were put together with a large group and they were transported to a prison back in Davao. It had been a hard core civilian prison for years, but now it housed 2000 American soldiers.

“I was in that prison for two years,” he says. “It was a self sufficient prison so prisoners went out in the rice fields and coffee plantation and worked day after day. I was lucky. My father had been a barber and I knew how to cut hair so they put me to work doing that. I began with only a few tools and soon I had clippers, scissors and they even built me a special chair so I could do the guys hair. I had to go out in the fields a few times, but I never did it for more than one day at a time.”

Life in a prison camp, especially a former prison is not easy, but it was not without it’s humor. The soldiers shoes wore out quickly and they had to make their own out of scrapes and wood. One guy fashioned his own version of walking pads.

“He made these big shoes that had a compartment inside,” relates Cline. “When he was out in the fields he stuffed the inside with rice so he would have extra food. One day he came back to the prison and he turned his ankle. The rice went all over the place and the guards went nuts. He had grown a beard that was about two feet long so to punish him they hung that shoe on his beard and he had to walk around with it attach to that beard for a long while. It was quite a site.”

In June of 1944, the Japanese began to move prisoners to Japan to work in their heavy industries, because many of their men had been conscripted to serve in the military. Cline and 1250 men were loaded on a cargo ship and sent off to Kyusho, the southern major island of the Japanese home islands. But the trip was scary, not only for the conditions but because American submarines were patrolling the waters and ships were constantly being sunk.

“When they took us out of the prison in Davao, there were 750 guys left there,” says Cline sadly. “A couple of months later they were put on a ship that was torpedoed by an American sub. Only 82 of them survived.”

Cline and his cohorts found themselves working in a copper refinery near Yokkaichi. He worked at that factory for nine months. During that time at the refinery American B-29’s attacked the city repeatedly.

“A few years later I went to the refinery in Magna (Kennecott’s refinery) and I found them using the exact same processes we were using in Japan.”

Nine months later he was moved to a steel mill near the city of Toyama to the north and on the coast. There he witnessed something that historians have labeled much worse that the dropping of the Atomic Bomb.

“The B-29’s would come in at 8000 feet and bomb the city with incidiary bombs,” he explains. “Those bombs would create firestorms so powerful that they would push up debris from the fires and send it into our camp five miles away. We were always putting out fires.”

In the camps in Japan the allies were not guarded by soldiers. Instead they were watched by what the allies termed “stick guards” men who carried long sticks and were civilians.

| Buss Cline today. |

“Those guys were not mean like the soldiers had been,” says Cline. “In fact they were mostly kind. One even sat me down one day and told me that we would be going home soon because the Japanese were losing the war.”

Three months later on August 14 the allied soldiers went back to their camp from the steel mill as usual for their noon meal. They were not called back to work that day. The next morning no one came to get them for work either. Later that day the camp commander came to the American commanding officer and told him the war was over. It was also Cline’s birthday.

“The Japanese commander asked what he could get us and even suggested he could get us girls,” said Cline laughing as he told the story. “None of us cared one bit about girls; all we wanted was food.”

The commander brought in a cow, it was slaughtered and then the camp feasted. A few days later they were taken to Tokyo and put on a hospital ship. When he was captured Cline weighed 130 lbs. When he was liberated he weighed 100 lbs.

“I didn’t lose much, but some of the guys in other camps were much worse off,” he says.

Cline returned to the United States with three physical injuries that he had received during the war, but more importantly he came back with post traumatic syndrome, something most people only associate with the Vietnam War. Many Americans had it, but it wasn’t publicized. He still dreams about things he saw. In fact the night before his interview for this story he had bad dreams about the experience.

“Think about it,” he said. “I was captured on May 10, Mother’s Day that year. This past Sunday was Mother’s Day.”

For the first 13 months of his captivity no one in his family, or Beth Turner who was waiting for him in Sunnyside knew if he was alive or dead. But the Japanese had a funny way of gloating about the allies they captured. They often broadcast the names of servicemen under their control and Cline’s name was heard by some people in Washington State on a short wave radio. Somehow they found his parents and contacted them to let them know he was alive.

When he returned to the United States he came back to Utah, married Beth and began to work for Utah Fuel Company. He did that for only six months and then he went to work for Geneva Mine, where he stayed a short 36 and one half years. Along with that job he also built, bought and ran three theaters in the East Carbon area, the drive in that used to be in town, the Esquire and the Nustar. He ran those for 29 years until they closed in 1979.

Cline, who lost Beth to a heart attack eight years ago still takes joy in life. He always traveled a lot, especially after retiring in 1982, and he still likes to but he says all the walking when you travel is starting to get to him. A few years ago he took his son and his daughter and their families to Italy for a visit.

“The Vatican’s a big place, you have to do a lot of walking there,” he says.

Some might think Cline thought those three years in the hands of an enemy were wasted, but he doesn’t. Each year he and the veterans he served time in the camp with get together. This year they met in Laughlin, Nev. but there were only 10 of them there. The generation that kept the world safe is passing on.

“You know, I wouldn’t want to go through being in the hands of the Japanese like that again, but then I wouldn’t trade the experience for a million dollars either,” he states adamantly.

Typical words from someone who hails from the greatest generation.